When you pick up a generic pill at the pharmacy, you expect it to work just like the brand-name version. But how does the FDA know it will? The answer lies in bioavailability studies - the quiet, science-heavy process that makes generic drugs safe, effective, and legal to sell. These aren’t just paperwork exercises. They’re rigorous clinical tests that measure whether your body absorbs the generic drug the same way it absorbs the original.

What Bioavailability Really Means

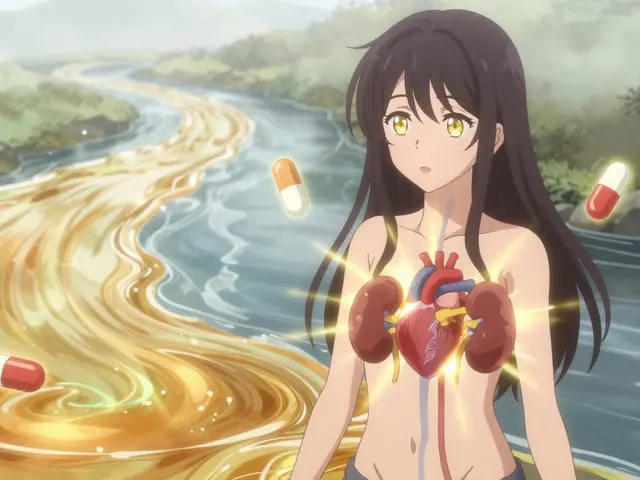

Bioavailability isn’t about whether a drug works in theory. It’s about what actually happens inside your body. Specifically, it measures two things: how much of the drug gets into your bloodstream, and how fast it gets there. This is critical because even if two pills contain the same active ingredient, differences in how they’re made - the fillers, coatings, or manufacturing process - can change how your body handles them. The FDA defines bioavailability as: “the rate and extent to which a therapeutically active chemical is absorbed from a drug product into the systemic circulation and becomes available at the site of action.” In plain terms: does your body get the same dose, at the same speed, from the generic as it does from the brand? To measure this, scientists track two key numbers: AUC (Area Under the Curve) and Cmax (Maximum Concentration). AUC tells you the total amount of drug your body is exposed to over time - think of it as the total dose delivered. Cmax shows you the peak level the drug reaches in your blood - this tells you how quickly it’s absorbed. A third number, Tmax (Time to Maximum Concentration), tells you when that peak happens. Together, these three values form the core of every bioequivalence study.How Bioequivalence Studies Work

A typical bioequivalence study for a generic pill involves 24 to 36 healthy volunteers. Each person takes both the brand-name drug and the generic version, in random order, with a break of at least five half-lives between doses to make sure no leftover drug interferes. Blood samples are taken every 30 minutes to two hours over 24 to 72 hours - depending on how long the drug stays in the body. These samples are analyzed using highly precise lab methods. The FDA requires that these methods be accurate within 85-115% of the true value, with precision (repeatability) better than 15%. It’s not enough to say “they look similar.” The data must be statistically rock-solid. The results are compared. If the generic’s AUC and Cmax are within 80-125% of the brand’s, it passes. But here’s the catch: it’s not just about the average. The FDA requires that the 90% confidence interval of the ratio between the two falls entirely within that 80-125% range. That means even the worst-case scenario - the lowest possible value - still has to be acceptable. This isn’t a guess. It’s a statistical guarantee that the difference is unlikely to be clinically meaningful. For example, if the brand’s average AUC is 100 units, the generic’s must be between 80 and 125 units. If the study shows the generic’s AUC is 116% of the brand’s, but the upper limit of the confidence interval hits 130%, the product fails - even though 116% sounds close. That’s because the FDA needs to be 90% sure the true difference won’t exceed 25% in either direction.Why the 80-125% Rule Exists

You might wonder: why 80-125%? Why not 95-105%? The answer comes from decades of clinical data and expert judgment. A 20% difference in absorption is generally not enough to change how a drug works for most people. Dr. John Jenkins, former director of the FDA’s Office of New Drugs, put it simply: “It’s not arbitrary. It’s based on clinical experience.” For most drugs - like antibiotics, blood pressure pills, or antidepressants - a 10-15% variation in absorption doesn’t cause noticeable changes in effectiveness or side effects. But there are exceptions. For drugs with a narrow therapeutic index - where the difference between a safe dose and a toxic one is tiny - the rules tighten. For drugs like warfarin, digoxin, or levothyroxine, the acceptable range narrows to 90-111% or even 90-112%. These are the drugs where even small changes can lead to serious problems: bleeding, heart rhythm issues, or uncontrolled seizures. That’s why some states require doctors to approve substitutions for these drugs. And why patient groups like the Epilepsy Foundation track reports of seizure changes after switching generics - even though the FDA found only 6.4% of those cases were likely tied to bioequivalence issues.

When Bioequivalence Isn’t Enough

Not all drugs are created equal - and not all generics are easy to test. For simple, immediate-release pills, the standard bioavailability study works well. But for complex products, the rules change. Take extended-release tablets. These are designed to release the drug slowly over hours. A standard AUC and Cmax comparison might miss differences in how the drug is released over time. The FDA now requires testing at multiple time points to ensure the release profile matches. Topical creams? Inhalers? Injectables? These don’t rely on blood levels. For a steroid cream, you can’t measure absorption through plasma - you measure skin thinning. For an inhaler, you measure lung deposition. For some drugs, the FDA accepts pharmacodynamic studies - where they measure a biological response, like blood pressure drop or reduction in inflammation - instead of blood concentrations. Then there are highly variable drugs, like tacrolimus or certain statins, where the same person’s absorption can vary wildly from day to day. For these, the FDA uses a special method called reference-scaled average bioequivalence (RSABE). It lets the acceptance range widen - up to 75-133% - if the drug naturally varies a lot. This prevents good generics from being rejected just because the body’s own biology makes absorption inconsistent.The BCS Waiver: When You Don’t Need a Study

Here’s a surprising fact: sometimes, you don’t need to test people at all. If a drug falls into the Biopharmaceutics Classification System (BCS) Class 1 - meaning it’s highly soluble and highly permeable - and the generic matches the brand exactly in ingredients and dissolution rate, the FDA may grant a waiver. No human studies needed. This is common for drugs like metformin, atenolol, or ranitidine. The science behind it is strong: if a drug dissolves completely in the gut and easily crosses into the bloodstream, then as long as the generic dissolves just as fast, it will behave the same. This saves time, money, and avoids unnecessary testing on healthy volunteers. BCS Class 3 drugs - highly soluble but poorly permeable - can also qualify if the generic is “qualitatively the same and quantitatively very similar” to the brand. This applies to drugs like cimetidine or acyclovir.Who Does These Studies - And How Much They Cost

Bioequivalence studies are run by contract research organizations (CROs) around the world. About 1,200 are conducted annually, valued at $1.8 billion. A single study can cost $250,000 to $500,000, depending on complexity. That’s why generics are cheaper: you’re not paying for new clinical trials. You’re paying for one bioequivalence study - and the cost is spread across millions of pills. The FDA has approved over 15,000 generic products since 1984. Today, 97% of U.S. prescriptions are filled with generics. Yet they make up only 26% of total drug spending. That’s the power of bioequivalence: it lets patients save money without sacrificing safety.The Future: AI, Modeling, and Better Tools

The field is evolving. In 2023, the FDA began exploring model-informed drug development - using computer models to predict bioavailability from formulation data. Early results from a collaboration with MIT show machine learning algorithms can predict AUC ratios with 87% accuracy across 150 drug compounds. This could reduce the need for human studies for simpler generics. For complex products - like inhalers or injectable suspensions - the FDA has issued 11 new product-specific guidances since 2023. These give manufacturers clear paths to prove equivalence without guesswork. Still, challenges remain. About 22% of generic applications in 2022 involved complex products - up from 8% in 2015. As drugs get more complicated, so do the tests. But the goal hasn’t changed: make sure every pill, no matter the label, delivers the same result.What Patients Should Know

If you’ve ever switched from a brand to a generic and felt something was off - a new side effect, less relief - you’re not alone. A small number of patients report changes. But for the vast majority, the difference is invisible. The FDA says 90% of people can’t tell the difference between brand and generic in real-world use. Most of the reported issues aren’t due to bioequivalence failure - they’re from changes in fillers, pill size, or even psychological expectations. If you’re on a narrow therapeutic index drug and notice changes after switching, talk to your doctor. Don’t assume the generic is bad. But don’t assume it’s always identical either. Your doctor can help determine if a switch is the cause - or if something else is going on. Bioavailability studies aren’t perfect. But they’re the best tool we have. And for over 40 years, they’ve kept millions of people healthy - at a fraction of the cost.Do bioavailability studies prove a generic drug is as safe and effective as the brand?

Yes. Bioavailability studies measure how much and how fast the active drug enters your bloodstream. The FDA’s 80-125% bioequivalence range is based on decades of clinical data showing that differences within this range are unlikely to affect safety or effectiveness for most drugs. While rare exceptions exist - especially with narrow therapeutic index drugs - the system has prevented virtually no therapeutic failures in conventional generics since 1984.

Why do some people say generics don’t work as well?

Most reports of problems come from patients on drugs with narrow therapeutic indexes - like levothyroxine, warfarin, or certain seizure medications. Small changes in absorption can matter here. But studies show that in over 90% of cases, the issue isn’t bioequivalence - it’s switching between different generic brands, changes in inactive ingredients, or inconsistent dosing habits. For most people, generics work exactly like the brand.

Can a generic drug fail bioequivalence testing?

Yes. If the 90% confidence interval for AUC or Cmax falls outside 80-125%, the product fails. This happens when the generic absorbs too slowly, too quickly, or inconsistently. Some generics fail multiple times before getting approved. Manufacturers often tweak the formulation - changing fillers, particle size, or coating - until it passes. The FDA doesn’t approve products that don’t meet the standard.

Are bioequivalence studies the same worldwide?

For most standard oral drugs, yes. The FDA, European Medicines Agency (EMA), and Japan’s PMDA follow nearly identical guidelines through the International Council for Harmonisation (ICH). The 80-125% range is global standard. Differences arise with complex products - like inhalers, gels, or extended-release forms - where regional guidance may vary slightly.

Why do some generics cost more than others?

The cost difference isn’t about bioequivalence - it’s about competition. If only one company makes a generic, it can charge more. Once multiple manufacturers enter the market, prices drop. Some generics use more expensive ingredients or complex manufacturing, which can raise costs. But if two generics are approved by the FDA, they’re equally effective. Price reflects market dynamics, not quality.

Comments (14)

Gabrielle Panchev

Wait-so you’re telling me that if my generic blood pressure pill has a Cmax that’s 124.9% of the brand, it’s perfectly fine, but if it’s 125.1%, it’s rejected? That’s not science-that’s bureaucratic magic. And don’t get me started on the 90% confidence interval… it’s like the FDA is trying to prove they’re better at math than a high school stats teacher with a caffeine addiction. Also, why does no one talk about how the same person’s absorption can vary 30% day-to-day due to stress, sleep, or what they ate for breakfast? We’re not machines. We’re biological messes wrapped in skin. And yet, we’re expected to trust a 24-person study from a CRO in Bangalore that cost less than my monthly Netflix subscription?

Dana Termini

I’ve been on generic levothyroxine for 8 years. I switched brands once because my insurance changed, and my TSH spiked. I went back to the original generic, and it stabilized. I’m not saying generics are bad-I’m saying consistency matters. The system works, but it’s not flawless. Patients need to know: if you feel different after a switch, it’s not all in your head. Track your labs. Talk to your doctor. And don’t let anyone tell you you’re being dramatic just because the FDA says 80–125% is safe.

Joann Absi

THE GOVERNMENT IS LYING TO YOU!!! 🚨

They let these Chinese generics pass because they’re paid off by Big Pharma! 😱

Did you know that the FDA’s lab equipment is 30 years old and calibrated by interns? 🤯

And why do you think they don’t test for heavy metals? BECAUSE THEY DON’T WANT YOU TO KNOW!!

My cousin’s dog got sick after eating a generic flea pill. That’s proof. 🐶💔

Wake up, sheeple. The pills are controlled by the Illuminati. 🕵️♀️🔮

They want you dependent. They want you weak. They want you buying pills instead of eating kale and meditating. 🌿🧘♀️

They’re not testing bioavailability-they’re testing your obedience. 🧠💊

Isaac Jules

Lmao. So the FDA says 80–125% is ‘clinically insignificant’? That’s like saying a 25% difference in your insulin dose won’t kill you. Have you met Type 1 diabetics? Or people on warfarin who’ve bled out because some generic’s Tmax was 20 minutes off? This isn’t ‘science.’ It’s corporate math dressed up in lab coats. And don’t even get me started on the CROs that run these studies-half of them have a 40% failure rate on audit. The FDA approves them anyway because they’re cheaper. You’re not getting ‘equivalent.’ You’re getting ‘good enough for the profit margin.’

Lily Lilyy

It’s amazing how much care goes into making sure generics work. I used to be scared to switch, but now I know the science behind it. It’s not magic-it’s hard work, careful testing, and real people doing the right thing. Thank you to everyone who makes this possible. You’re helping so many people save money and stay healthy. Keep doing the good work. 💪❤️

Stuart Shield

I love how this post doesn’t just dump data-it tells a story. It’s like reading a detective novel where the villain is ‘inconsistent dissolution rates’ and the hero is a 24-person study in a sterile clinic. The 80–125% rule? It’s not arbitrary-it’s the result of decades of trial, error, and quiet brilliance. And the BCS waiver? Genius. It’s like saying, ‘Hey, if this molecule is basically a water-soluble bullet, why make healthy people swallow pills just to prove it works?’ We don’t need to test everything. Sometimes, the smartest thing is to trust the chemistry.

Jeane Hendrix

So… if a drug is BCS Class 1, you don’t need human trials? That’s wild. I always thought they had to test on people. But if the drug dissolves the same and absorbs the same… why test people at all? It makes sense, but also feels kinda… scary? Like, what if the dissolution profile changes slightly during shipping? Or if the tablet gets exposed to humidity? Do they test that? Or is it just ‘assume it’s fine’? I need more info. 😅

Rachel Wermager

RSABE is the real MVP here. For highly variable drugs like tacrolimus, the standard 80–125% would reject 90% of generics. RSABE accounts for intra-subject variability-meaning it doesn’t punish a drug just because your body is a fickle beast. It’s a statistically elegant solution to a messy biological problem. Also, the FDA’s move toward model-informed development? Long overdue. If you can simulate AUC with ML accuracy of 87% across 150 compounds, why waste 500K on a 24-person trial? The future is computational pharmacokinetics. Get ready.

Kelly Beck

Just wanted to say-this is the kind of post that makes me believe in humanity again. 🌟

So many people think generics are ‘cheap and risky,’ but this breaks down exactly why they’re not. It’s not just about cost-it’s about access. People who can’t afford brand-name meds? They’re not taking shortcuts. They’re taking science. And the FDA’s standards? They’re tough. Rigorous. Thoughtful.

Thank you for writing this. I’m sharing it with my mom who’s on generic statins and thinks they’re ‘fake medicine.’ She’s gonna read this. And maybe, just maybe, she’ll stop worrying. 💙

Wesley Pereira

So the FDA lets you skip human trials for metformin? Cool. So if I make a metformin tablet out of crushed-up brand pills and sprinkle them into a sugar cube… does that pass BCS Class 1? 😏

Because ‘highly soluble and highly permeable’ doesn’t mean ‘can be made in a garage with a coffee grinder.’

But hey, if the math says it’s fine, I guess we just trust the algorithm. 🤖💊

Meanwhile, my cousin’s dog is still sick from the generic flea pill. 🐶

Melanie Clark

They’re hiding something… I know it. Why do they never talk about the fact that generics are often made in the same factories as the brand? Same machines. Same batch numbers. Same workers. Why call it ‘generic’ if it’s literally the same pill? It’s a scam. They’re just rebranding. And the FDA? They’re in on it. They don’t want you to know you’re paying extra for the label. The pill is the same. The price should be the same. But they make you think you’re getting ‘less’-so you pay more for the brand. It’s psychological manipulation. And the ‘bioequivalence’? A distraction. A smokescreen. A corporate illusion. 💸👁️

Saylor Frye

Wow. So the FDA’s 80–125% range is basically the pharmaceutical version of ‘close enough.’

Meanwhile, my phone’s battery health drops 10% a year and Apple sends me a ‘replace now’ alert.

But my blood pressure med can be 25% off and I’m supposed to be chill?

Also, ‘model-informed drug development’ sounds like a Silicon Valley startup trying to replace doctors with a chatbot.

Anyway. I still take my generic. But now I’m weirdly suspicious of it. 🤔

Mukesh Pareek

BCS Class 1: high solubility, high permeability-this is foundational pharmacokinetics. But you're missing the point: dissolution rate is not synonymous with bioavailability. The particle size distribution, crystalline form, and surfactant content are critical. Most generic manufacturers optimize for cost, not pharmacodynamic fidelity. The 80–125% CI is a statistical fiction masking heterogeneity in real-world absorption. You need in vivo-in vitro correlation (IVIVC) models, not just AUC/Cmax. Without IVIVC, you're flying blind. And don't get me started on the lack of post-marketing pharmacovigilance for generics. The system is brittle.

Katelyn Slack

Just wanted to say thank you for this. I’m a nurse and I get asked this all the time. I never knew the details behind the 80–125% rule. Now I can actually explain it to patients without sounding like a textbook. Also, I had no idea about the BCS waiver-that’s so cool. I’m gonna print this out and keep it in my binder. 💕