GERD is gastroesophageal reflux disease, a chronic condition where stomach acid frequently flows back into the esophagus. Laryngopharyngeal reflux (LPR) is a form of acid reflux that reaches the larynx and pharynx, causing throat‑related symptoms. Most people think of heartburn when they hear "reflux," but the reality is broader: the same backflow of acid can irritate the throat, voice box, and even the ears. This article breaks down how GERD and LPR are linked, where they diverge, and what you can do to keep both under control.

What Exactly Is GERD?

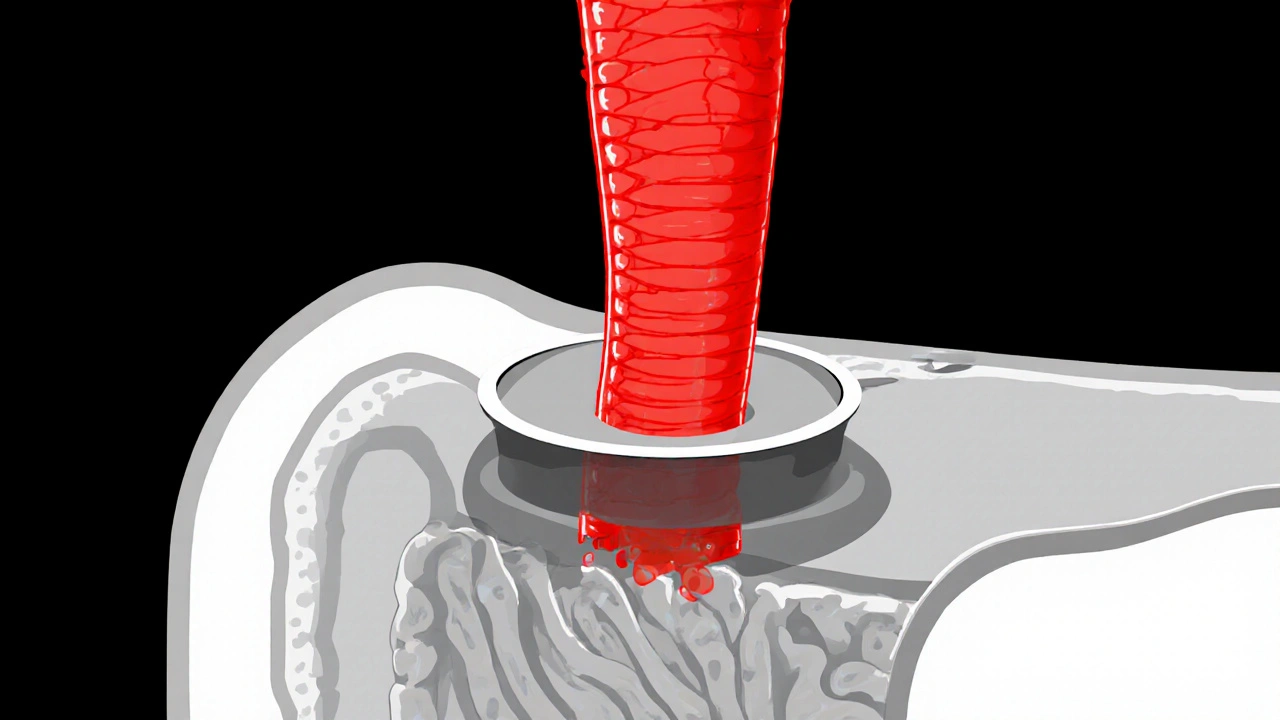

GERD occurs when the lower esophageal sphincter (LES) fails to stay closed after a meal. The LES is a ring of muscle at the bottom of the Esophagus that acts like a valve. When it relaxes inappropriately, stomach contents - mainly acid and digestive enzymes - splash back up.

Typical symptoms include:

- Burning chest pain (classic heartburn)

- Sour taste in the mouth

- Regurgitation of food or liquid

- Difficulty swallowing (dysphagia)

Defining Laryngopharyngeal Reflux (LPR)

Unlike GERD, LPR doesn’t always produce heartburn. The refluxed material travels higher, passing the LES, moving through the Upper Esophageal Sphincter (UES), and reaching the Larynx and Pharynx. The lining of these structures is more delicate than the esophagus, so even small amounts of acid or pepsin can cause irritation.

Common LPR symptoms include:

- Persistent throat clearing

- Hoarseness or a “croaky” voice

- Feeling of a lump in the throat (globus sensation)

- Chronic cough, especially at night

- Sore throat without obvious infection

Shared Anatomy and Mechanisms

Both GERD and LPR start with the same basic problem: reflux of gastric contents. The key anatomical players are:

- Esophagus - the tube that carries food from mouth to stomach.

- Lower Esophageal Sphincter (LES) - keeps stomach acid down.

- Upper Esophageal Sphincter (UES) - prevents backflow into the throat.

- Larynx and Pharynx - structures that can be damaged by acid.

- Hiatal hernia - a condition where part of the stomach pushes up through the diaphragm, weakening the LES.

When the LES is weak, acid can reach the esophagus (GERD). If the UES also fails, that same acid can climb higher, causing LPR. In many patients, both sphincters are compromised, leading to overlapping symptoms.

Symptoms: Where GERD and LPR Overlap and Where They Differ

| Symptom | Typical in GERD | Typical in LPR |

|---|---|---|

| Heartburn | ✔️ | ❌ (rare) |

| Regurgitation | ✔️ | ❌ (rare) |

| Throat clearing | Occasional | ✔️ |

| Hoarseness | Occasional | ✔️ |

| Chronic cough | Sometimes | ✔️, especially at night |

| Globus sensation | Rare | ✔️ |

The table shows why many clinicians treat both conditions together: a patient may report heartburn and hoarseness, meaning both the esophagus and throat are being exposed to acid.

How Doctors Diagnose GERD and LPR

Diagnosis often starts with a detailed history and a physical exam. For GERD, doctors may use:

- Empiric trial of a proton pump inhibitor (PPI) for 8‑12 weeks.

- Upper endoscopy to look for esophagitis, strictures, or Barrett’s esophagus.

- 24‑hour pH monitoring to measure acid exposure.

- Flexible laryngoscopy to view the vocal cords and look for redness, edema, or posterior commissure hypertrophy.

- Dual‑probe pH or impedance testing that records acid in both the esophagus and the pharynx.

- Pepsin detection in saliva - a newer, non‑invasive test gaining traction.

Accurate diagnosis helps tailor treatment, especially when lifestyle changes alone aren’t enough.

Treatment Strategies That Cover Both Conditions

Because GERD and LPR share a root cause, many interventions overlap. Here’s a practical roadmap:

1. Lifestyle Adjustments

- Diet tweaks: Limit citrus, tomato‑based foods, chocolate, caffeine, and mint. Opt for smaller, more frequent meals.

- Weight management: Even a 5‑10% weight loss can reduce LES pressure.

- Elevate the head: Raise the bedside by 6‑8 inches to keep acid from creeping up while you sleep.

- Quit smoking and reduce alcohol: Both relax the LES and increase acid production.

- Clothing: Avoid tight belts or waistbands that squeeze the stomach.

2. Medications

- Proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) - the most powerful acid suppressors (e.g., omeprazole, esomeprazole). Usually taken 30minutes before breakfast.

- H2‑blockers - less potent than PPIs but useful for on‑demand relief (e.g., ranitidine, famotidine).

- Alginate‑based therapies - form a foam “raft” that floats on top of stomach contents, protecting the LES and UES (e.g., Gaviscon).

- Prokinetics - help the stomach empty faster, reducing reflux pressure (e.g., metoclopramide).

3. Targeted Therapies for LPR

- Voice therapy with a speech‑language pathologist to reduce vocal strain.

- Antireflux diet specifically timed so the last meal finishes at least 3 hours before bedtime.

- Saliva pepsin testing can guide whether acid suppression needs to be intensified.

4. Surgical Options

When medication and lifestyle changes fail, procedures such as laparoscopic Nissen fundoplication (tightening the LES) or magnetic sphincter augmentation (LINX device) can restore barrier function. These are considered after 6‑12 months of optimal medical therapy.

When to Seek Professional Help

If you experience any of the following, schedule a visit promptly:

- Difficulty swallowing or feeling food stuck.

- Unexplained weight loss.

- Frequent vomiting or vomiting blood.

- Hoarseness persisting beyond two weeks despite home remedies.

- Chronic cough that interferes with sleep or daily activities.

Early assessment reduces the risk of complications like esophageal stricture, Barrett’s esophagus, or permanent vocal cord damage.

Practical Tips to Keep Both Conditions in Check

- Track your meals and symptoms in a simple diary. Note triggers, timing, and severity.

- Adopt a “no‑eating‑after‑7PM” rule on weekdays; allow a longer fasting window on weekends.

- Invest in a good pillow that elevates your head without causing neck strain.

- Stay hydrated, but avoid large gulps of water right after meals.

- Schedule a follow‑up endoscopy or pH study if symptoms persist after 12 weeks of PPI therapy.

Small, consistent changes often beat drastic diets or endless medication switches.

Frequently Asked Questions

Can GERD cause LPR, or are they separate conditions?

They share the same root problem-acid reflux-but LPR occurs when the reflux reaches the throat. So GERD can lead to LPR, especially if the upper esophageal sphincter is also weak.

Why don’t I feel heartburn even though I have LPR?

The laryngeal and pharyngeal tissues are more sensitive to small amounts of acid or pepsin, so irritation shows up as throat symptoms rather than the classic burning sensation in the chest.

Are PPIs enough to treat LPR?

PPIs reduce acid production and help many patients, but LPR may also need alginate therapy, dietary changes, and voice rehab. A combined approach gives the best odds.

How long should I stay on a PPI?

A typical trial lasts 8‑12 weeks. If symptoms resolve, many doctors taper to the lowest effective dose or switch to an H2‑blocker for maintenance.

Can surgery cure both GERD and LPR?

Surgical reinforcement of the LES (e.g., Nissen fundoplication) often eliminates reflux at its source, which can also stop reflux from reaching the throat. Success rates are high, but surgery is considered only after meds and lifestyle fixes fail.

Comments (16)

John Babko

Listen up, folks!!! This GERD vs LPR talk is just another example of how American fast‑food culture is wrecking our throats!!! If you keep guzzling burgers and soda, don't be surprised when your esophagus throws a tantrum!!! The solution? Eat like a real American-moderation, leafy greens, and a side of common sense!!!

Stacy McAlpine

Totally agree, cutting back on coffee and chocolate can really calm the acid flow. Small changes in diet make a big difference.

Hanna Sundqvist

i read the part about pepsin in spit and think thats some kind of hoax, like big pharm don't want u to know.

Jim Butler

Thank you for this comprehensive overview of GERD and LPR; it is both enlightening and actionable.

The detailed comparison of symptoms clarifies why many patients experience overlapping issues.

I appreciate the emphasis on lifestyle modifications as the first line of defense.

Reducing portion size and avoiding trigger foods such as chocolate and citrus can markedly lower reflux incidents.

Elevating the head of the bed by six to eight inches is a simple yet often overlooked strategy.

Weight management, even a modest five‑percent reduction, has been shown to improve lower esophageal sphincter pressure.

Smoking cessation and limiting alcohol intake further support sphincter competence.

Pharmacologic therapy, particularly proton pump inhibitors, offers potent acid suppression when lifestyle changes are insufficient.

However, long‑term PPI use should be monitored for potential adverse effects, and stepping down to the lowest effective dose is prudent.

Alginate‑based formulations provide a mechanical barrier that can protect both the esophagus and the upper sphincter.

For patients with persistent throat symptoms, a referral to a speech‑language pathologist for voice therapy is valuable.

Dual‑probe pH monitoring or salivary pepsin testing can pinpoint whether reflux reaches the larynx.

Surgical options such as laparoscopic Nissen fundoplication remain effective for refractory cases.

It is essential to individualize treatment plans, balancing medication, diet, and possible intervention.

Ultimately, patient education and consistent follow‑up empower individuals to manage their condition successfully. 😊

Ian McKay

While the information presented is thorough, it is recommended that the author verify the latest guidelines regarding prolonged PPI usage. Additionally, the description of alginate therapy could be clarified for lay readers.

Deborah Messick

It is presumptuous to assert that dietary adjustments alone are sufficient for all patients. Many individuals possess genetic predispositions that render lifestyle changes marginal at best. Therefore, a more critical appraisal of the evidence is warranted.

Renee van Baar

Everyone's experience with reflux can vary widely; while some may indeed need medication from the outset, encouraging patients to track their triggers can still provide valuable insights. A collaborative approach that blends mentorship with personalized data often yields the best outcomes.

Janice Rodrigiez

Think of your throat like a delicate garden-acid is the herbicide that can wilt blossoms. Swap soda for sparkling water, and let your vocal cords breathe. Simple swaps keep the landscape thriving.

Jonathan Seanston

Hey Janice, love the garden analogy! It really paints a vivid picture of how we can protect our voice.

Sukanya Borborah

While the metaphor is cute, it oversimplifies the pathophysiology; reflux involves complex sphincter dynamics and pepsin activity, not just "herbicide". A more nuanced discussion would benefit clinicians.

Stu Davies

Reading through all this can be overwhelming, but you’re not alone in navigating GERD and LPR. Many have walked this path and found relief with patience and support 🤗

Nadia Stallaert

Isn't it absurd!!! That our bodies betray us with hidden fire while we sleep!!! The silent siege on our throats is a conspiracy of biology and modern lifestyle!!! Wake up, people!!!

Greg RipKid

Honestly, if you skip late-night snacks and keep your head elevated, you’ll notice a big drop in night coughs. It’s a simple tweak that works for most.

John Price Hannah

Wow, Greg, your laid‑back advice sounds like a lazy bedtime story!!! Where’s the real science? People need hard‑hitting facts, not sugar‑coated lullabies!!!

Echo Rosales

Not everyone benefits from blanket PPI recommendations.

Elle McNair

True, treatment should be tailored to each individual's needs.